Endless Mayfly’s Ephemeral Disinformation Campaign

By Gabrielle Lim, Etienne Maynier, John Scott-Railton, Alberto Fittarelli, Ned Moran, and Ron Deibert

May 14th, 2019, The CitizenLab

https://citizenlab.ca/2019/05/burned-after-reading-endless-mayflys-ephemeral-disinformation-campaign/

Endless Mayfly1 is an Iran-aligned network of inauthentic websites and online personas used to spread false and divisive information primarily targeting Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel. Using this network as an illustration, this report highlights the challenges of investigating and addressing disinformation from research and policy perspectives.

Key Findings

- Endless Mayfly is an Iran-aligned network of inauthentic personas and social media accounts that spreads falsehoods and amplifies narratives critical of Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel.

- Endless Mayfly publishes divisive content on websites that impersonate legitimate media outlets. Inauthentic personas are then used to amplify the content into social media conversations. In some cases, these personas also privately and publicly engage journalists, political dissidents, and activists.

- Once Endless Mayfly content achieves social media traction, it is deleted and the links are redirected to the domain being impersonated. This technique creates an appearance of legitimacy, while obscuring the origin of the false narrative. We call this technique “ephemeral disinformation”.

- Our investigation identifies cases where Endless Mayfly content led to incorrect media reporting and caused confusion among journalists, and accusations of intentional wrongdoing. Even in cases where stories were later debunked, confusion remained about the intentions and origins behind the stories.

- Despite extensive exposure of Endless Mayfly’s activity by established news outlets and research organizations, the network is still active, albeit with some shifts in tactics.

Summary

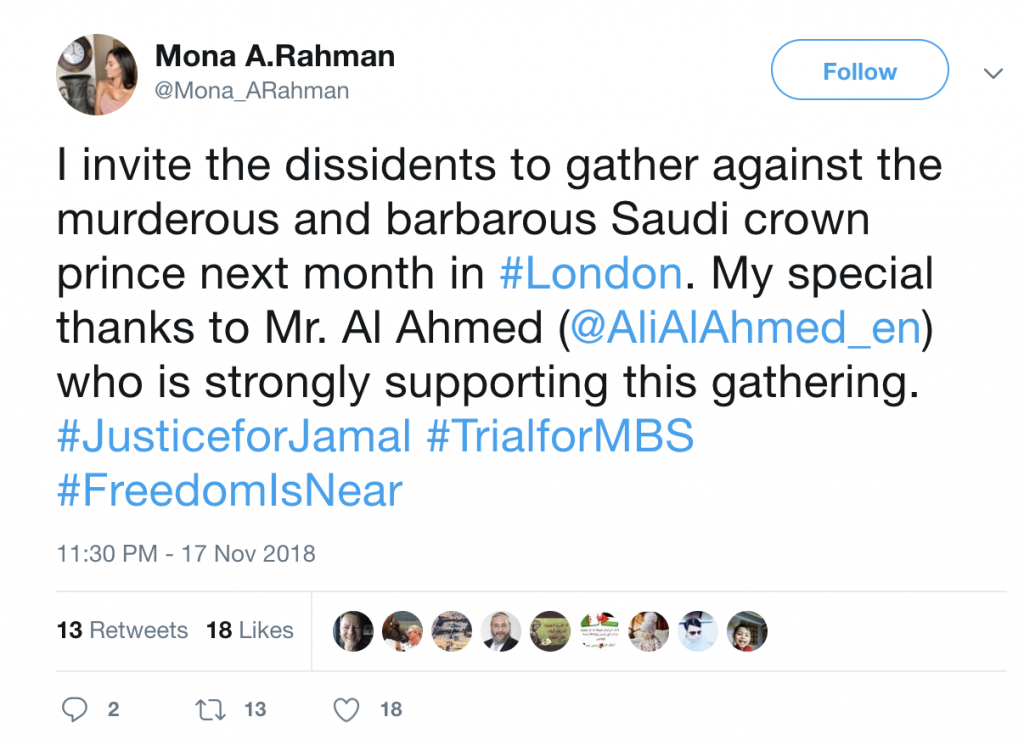

On November 5, 2018, Ali Al-Ahmed, a Washington-based expert in terrorism in the Gulf states and a vocal critic of Saudi Arabia, received a direct message on Twitter from “Mona A. Rahman” (@Mona_ARahman).

After engaging in some polite conversation in Arabic with Al-Ahmed, “Mona” shared what appeared to be an article from the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center (see Figure 1). The article contained a purported quote from former Mossad director Tamir Pardo, alleging that former Israeli Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman had been dismissed by Netanyahu for being a Russian agent. These allegations, if true, might reasonably be expected to strain relations between Russia and Israel.

The article appeared superficially genuine, even if the claim was startling. The colours, typeface, logo, and layout were identical to the Belfer Center’s website. But Al-Ahmed, who had recently been the target of a phishing campaign by hackers impersonating real journalists, was suspicious. A closer look at the article revealed typos, bad grammar, and a suspicious URL. The article was hosted on belfercenter[.]net, not belfercenter.org, which is the genuine Belfer Center’s website.

Who Was Mona A. Rahman?

A purported “Political Analyst & Writer,” Mona A. Rahman appeared to be a critic of the Saudi government. Many of her tweets expressed anger over the murder of journalist and Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi, who, according to multiple sources (including the C.I.A. and Turkish officials) was assassinated at the behest of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Like Al-Ahmed, “Mona” had pinned a tweet urging people to attend a counter-Saudi protest in London. Her tweet thanked him for his support of the issue (see Figure 2) .

Mona A. Rahman’s earlier Twitter history showed that she had engaged in spam-like behaviour, repeatedly tweeting dubious links—behaviour that raises questions about her authenticity. Al-Ahmed also noted to Citizen Lab researchers that her Arabic chat with him contained telling mistakes, including the accidental use of the Persian character چ.

More Fake People, More Targets

Al-Ahmed was not the only figure to be sent the inauthentic article. Lahav Harkov, a contributing editor for The Jerusalem Post, had been contacted by a “Bina Melamed” (@binamelamed)2 on Twitter via a mention. Like “Mona,” “Bina” was also promoting the inauthentic Belfer Center link. Harkov and other reporters called the persona3 out online. Eventually the case made the Israeli news. “Bina” also contacted Amy Spiro, a reporter for The Jerusalem Post, but when Spiro called the persona a “fake troll,” “Bina” tweeted screenshots of their private direct messages, accusing Spiro of tweeting for fame. Later, “Bina” changed her name to “Leakers Without Borders” and again began engaging journalists with another false story.

Introducing Endless Mayfly

Al-Ahmed, Harkov, and Spiro were among many journalists pitched stories by an extensive influence and disinformation operation that we call Endless Mayfly. Employing multiple tactics, personas, and narratives, Endless Mayfly seeks to amplify geopolitical tensions by propagating stories critical of Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel. Not only did the network regularly attempt to build relationships with journalists and activists like Al-Ahmed as a means to further amplify disinformation, it was also responsible for a wide set of fraudulent articles, domains, and social media accounts (see Figure 3). We define disinformation as false information that is disseminated with the deliberate intent to mislead or deceive.

Initial reporting on some of the inauthentic articles speculated that Endless Mayfly may have links to Russia; however, based on the evidence gathered from our investigation we conclude with moderate confidence that Endless Mayfly is Iran-aligned and has been operational since at least early 2016. This level of confidence is based on the overall framing of the campaign, the narratives used, and indicators from overlapping data in other reports.

Many of the inauthentic articles linked to Endless Mayfly have been publicly identified and debunked by journalists or the target news outlets themselves. In 2016, for example, Buzzfeed News published a piece on an inauthentic Guardian article, while Le Soir wrote about how they were impersonated in 2017. In August 2018, accounts and pages related to the republishing network used by Endless Mayfly were deactivated by Facebook in coordination with FireEye. Google and Twitter followed suit shortly after, citing “state-sponsored activity” and “coordinated manipulation” as reasons for the account shutdowns respectively. The network is still active at the time of writing, although its activity levels and tactics have evolved since we first began observing it.

Ultimately, the impacts of Endless Mayfly’s disinformation campaigns are difficult to measure. While there is evidence that there was some interaction with the inauthentic articles and personas based on the number of clicks, retweets, and coverage from mainstream media, it is unclear to what extent the operations swayed public opinion.

Report Roadmap: Ephemerality and Experimentation

This report employs a multidisciplinary approach to track and understand Endless Mayfly’s multi-platform, multi-narrative disinformation campaign. We use infrastructure analysis and open source intelligence techniques to characterize the scope and nature of Endless Mayfly’s Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs). This technical research is paired with discourse analysis to understand the narratives Endless Mayfly deploys and leverages as part of their efforts to influence online conversations and, ultimately, attempt to achieve political outcomes.

We pay special attention to Endless Mayfly’s extensive use of ephemerality (by intentionally deleting content once it has been amplified) and tactical experimentation when seeding narratives, and reflect on what this means for the future of disinformation online. We discuss how these techniques can frustrate efforts by researchers to understand the objectives of a campaign and reach conclusive attribution.

Every disinformation campaign is different and the overall landscape of disinformation practices is still in flux. However, we see Endless Mayfly as part of a trend towards more complex, multi-narrative, multi-platform efforts that evolve over time. Such campaigns cannot be fully understood, or countered, without using a wide range of tools that cut across traditional disciplinary silos, such as information security, political science, journalism, and education. This report is intended as a deep dive into Endless Mayfly and a presentation of a reusable set of methods for investigating complex, multi-platform disinformation operations.

Research Methods & Scope

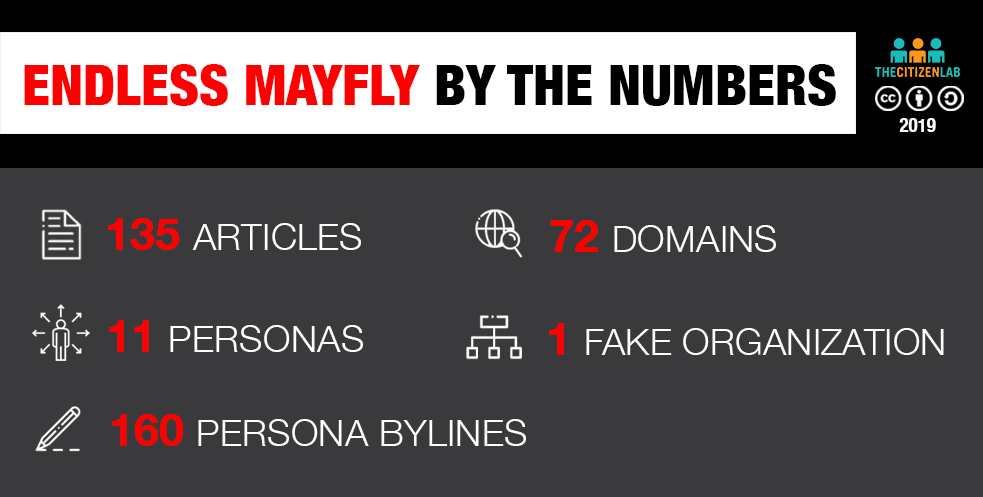

Our investigation began in April 2017 when we identified an inauthentic article that had been posted to Reddit, which was subsequently called out by other Redditors for being dubious and false. Using that initial article, domain, and persona as a starting point, we were able to identify other personas, domains, and articles affiliated with the network. This “snowballing” technique led us to 135 inauthentic articles, 72 domains, 11 personas, one fake organization, and a pro-Iran republishing network—all ostensibly serving Iranian interests.

The scope of the content collected and analysed is limited to Twitter activity, the inauthentic articles and domains, persona-attributed articles and posts, and third-party websites that either linked back to or referenced the inauthentic articles. Data was collected in English, French, and Arabic, while analysis was conducted in English. Where necessary, French and Arabic content was translated into English prior to analysis. For a more detailed explanation of our methods, see Appendix B: Domain Infrastructure and Appendix C: Narrative Analysis.

The study of media manipulation has grown to encompass many disciplines and offers just as many definitions of efforts to manipulate opinion. We situate this investigation within the field that explicitly studies disinformation. Endless Mayfly’s observable online behaviour is a disinformation operation and we use this term to frame our analysis. By disinformation we mean false information that is disseminated or propagated with the deliberate intent to mislead and deceive. Because Endless Mayfly sits within the broader discourse of information operations and media manipulation, we are also publishing a detailed annotated bibliography on disinformation research as a companion to this report. This report can be found here.

Report Sections

This report is organized into the following sections:

Part 1: The Endless Mayfly Disinformation Supply Chain provides an overview of the technical and non-technical tactics used by Endless Mayfly to create and propagate false content.

Part 2: Endless Mayfly’s Preferred Narratives describes the narratives being reinforced by the personas and inauthentic articles.

Part 3: Content Consumption and Impact describes the observable impact of Endless Mayfly’s activity.

Part 4: Hints of a Linked Malware Campaign describes evidence linking Endless Mayfly to a malware campaign targeting Android and Windows devices.

Part 5: Analysis of Competing Hypotheses assesses the most likely actors behind Endless Mayfly.

Part 6: Discussion concludes with a discussion regarding the Internet as a “disinformation laboratory,” ephemeral evidence, and the challenges associated with documenting and countering disinformation.

Part 1: The Endless Mayfly Disinformation Supply Chain

An overview of the supply chain developed by Endless Mayfly to disseminate disinformation

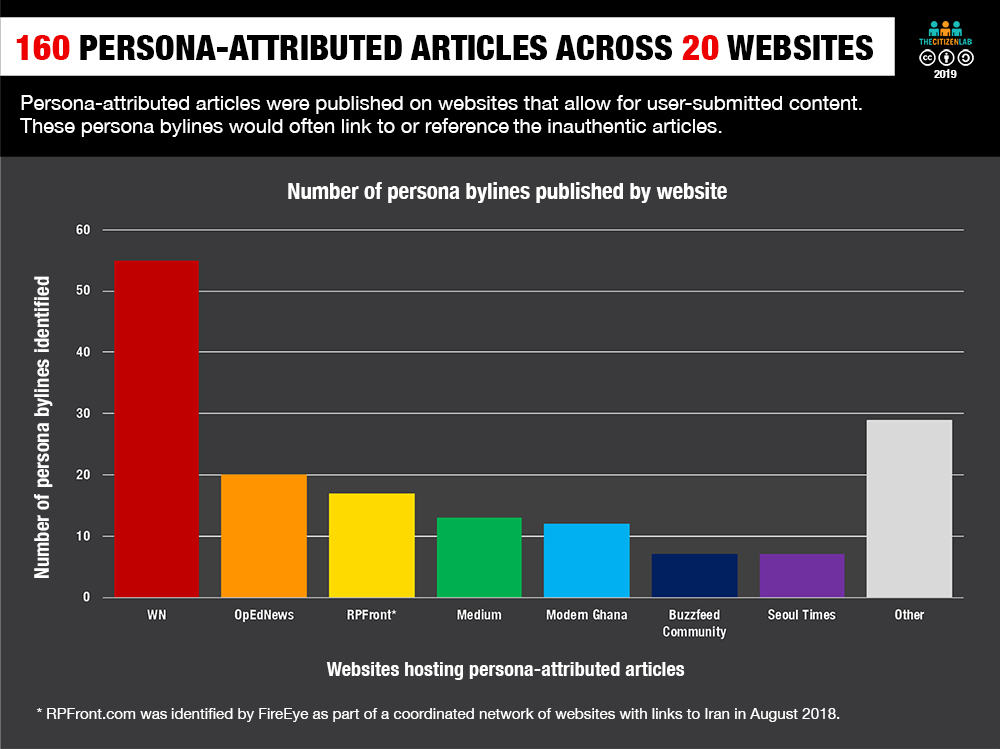

Our investigation tracks the Endless Mayfly network between April 2016, when the first known Twitter persona associated with the network was created, to November 2018. During this period, we monitored the personas’ Twitter activity, the reach of their content, and engagement with journalists and other figures online. In total, we identified 135 inauthentic articles, 72 domains, 11 personas, 160 persona bylines4, and one false organization (see Figure 3).

Multiple Phases of Activity

Endless Mayfly adapted and experimented throughout our investigation. These changes are grouped into four somewhat-overlapping phases of activity with each phase exhibiting distinct features, such as the creation and amplification of a false organization (Phase 1) or the use of private messaging to established journalists (Phase 4). See Table 1 below for a detailed description of the phases.

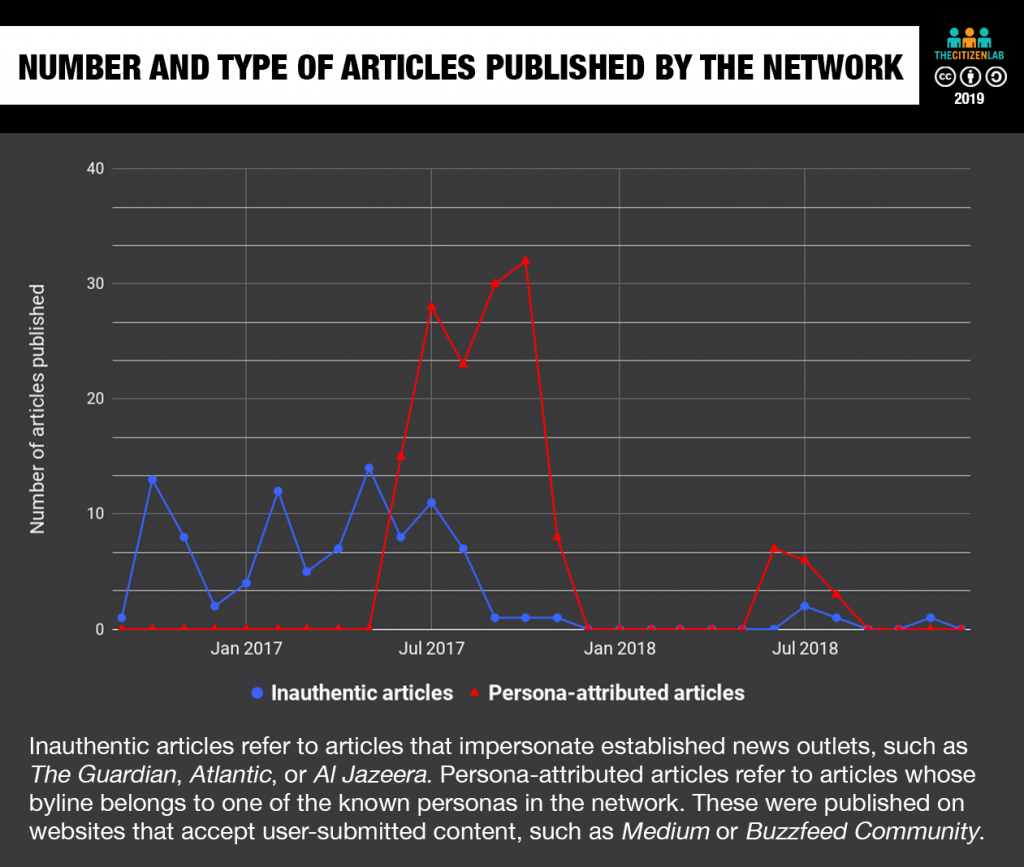

One of the most dramatic shifts in tactics occurred in June 2017, when the network transitioned from primarily amplifying inauthentic articles published on websites that they controlled, to persona-attributed articles on third-party sites (see Figure 4). The drivers of these shifts are unclear and may be explained by responses to disclosure and blocking, a pre-planned strategy, or simply experimentation. For a deeper analysis of each phase, see Appendix A.

The Four Phases of Endless Mayfly

| Phase | Time frame | Key activity |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | April 2016 – April 2017 | Six personas associated with an organization calling itself the Peace, Security, and Justice Community (@PSJCommunity) promote inauthentic articles and stories critical of Saudi Arabia on Twitter. |

| 2 | April 2017 – October 2017 | Creation and dissemination of inauthentic articles continues in addition to three new personas. The new personas pen their own articles while seeking collaboration with real-life journalists and activists. |

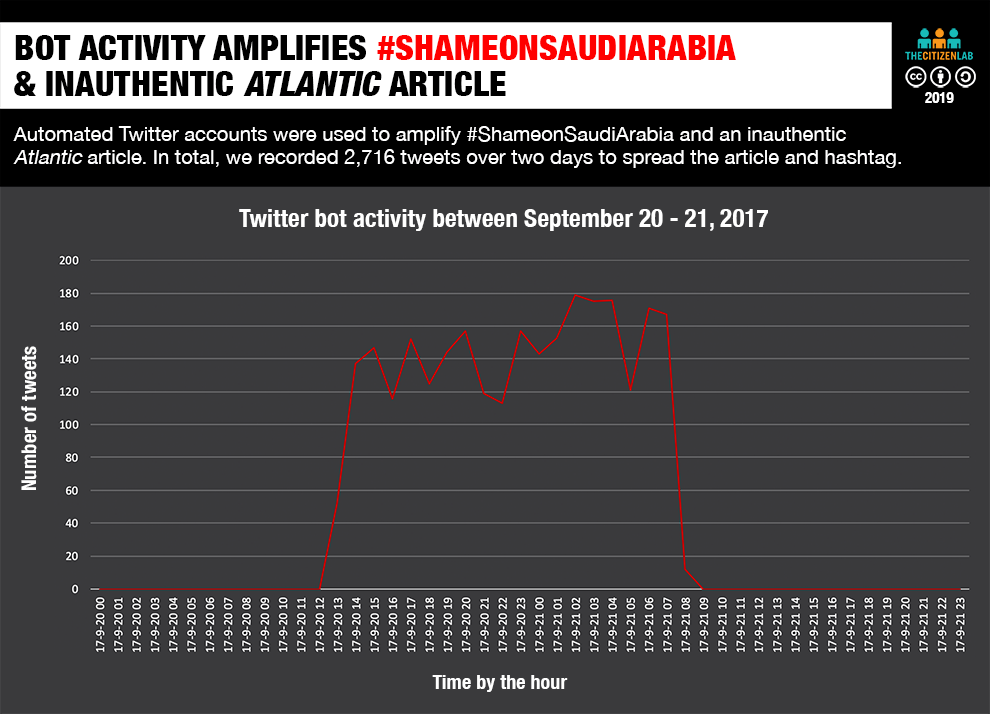

| 3 | August 2017 – November 2017 | Creation of inauthentic and persona-penned articles declines sharply. Instead, Twitter bots are used to drive traffic to an inauthentic Atlantic article and promote the #ShameOnSaudiArabia hashtag. |

| 4 | December 2017 – November 2018 | Inauthentic articles and personas continue to emerge at a diminished rate. Private contact with journalists begins. |

Table 1: Summary of the four phases of Endless Mayfly. Full analysis of each phase can be found in Appendix A

The Disinformation Creation and Amplification Process

Although Endless Mayfly’s chronological activity can best be described as four overlapping phases, the objective of each phase remained the same: to create, disseminate, and amplify false and misleading content. We refer to this sequence as a “disinformation supply chain,” which can broadly be summarized into the following five steps:

Step 1: Create personas: Endless Mayfly personas establish social media identities that are used to amplify specific narratives and propagate Endless Mayfly content.

Step 2: Impersonate established media sites: Using typosquatting and scraped content, sites are created to impersonate established media outlets, such as Haaretz and The Guardian, which then serve as platforms for the inauthentic articles.

Step 3: Create inauthentic content: Stories combining false claims and factual content are published on the copycat sites or as user-generated content on third-party sites.

Step 4: Amplify inauthentic content: Endless Mayfly personas amplify the content by deploying a range of techniques from tweeting the inauthentic articles to privately messaging journalists. Multiple Iran-aligned websites also propagate content in some instances. In one case, bot activity was observed on Twitter.

Step 5: Deletion and redirection: After achieving a degree of amplification, Endless Mayfly operators deleted the inauthentic articles and redirected the links to the legitimate news sites that they had impersonated. References to the false content would continue to exist online, however, further creating the appearance of a legitimate story, while obscuring its origins.

The following section provides a description of this supply chain. As a simplification, the section is organized by steps in the creation and dissemination of disinformation; however, this way of organizing is not intended to indicate a rigid chronology. Personas (“Step 1”) and content (“Steps 2 & 3”) were created throughout the years that Endless Mayfly was active.

Step 1: The Endless Mayfly Personas

The personas created by Endless Mayfly were typically thin, with limited depth beyond a Twitter bio and a history of tweeting on a narrow band of topics. Personas included fake students, journalists, and activists (see Table 2). As the campaign matured, some of the personas achieved somewhat greater depth by obtaining bylines on third-party websites and publishing content under their own name.

| Twitter handle | Location | Creation date | Twitter bio | Phase of Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JoliePrevoit | Paris | 12/4/2016 | “freelancer;hyperpolyglot:Deutsch,English,un poco español,français,un po ‘di italiano,العربية;#HumanRights & civil society activists, advocates for reform,” | Phase 1 |

| eliana_badawi | Europe | 3/8/2016 | “freelance journalist, Muslim, anti-Wahhabism (terrorism), works at @PSJCommunity” | Phase 1 |

| Shammari_Tariq | New York | 27/4/2017 | “Online Activist | Covering the latest from Saudi Arabia | Freedom. Justice. Equality. Let’s get to work!” | Phase 2-4 |

| Brian_H_Hayden | Paris | 21/5/2017 | ”freelancer;hyperpolyglot:Deutsch,English,un poco español,français,un po ‘di italiano,العربية;#HumanRights & civil society activists, advocates for reform.” | Phase 2 |

| binamelamed | London | 18/1/ 2010 | “Human rights activist, Freelance journalist, Enjoy politics, activism and martial arts.” | Phase 4 |

Table 2: Sample of Endless Mayfly personas on Twitter

These Twitter personas amplified content from three sources: Endless Mayfly-hosted disinformation, content published under their names on third-party sites, and assorted content from unaffiliated, third-party sites.

Steps 2 & 3: Lookalike Domains & Copycat Content

Endless Mayfly created at least 135 inauthentic articles and 72 lookalike domains that they controlled. Most of these domains impersonated well-known media outlets, although a small handful masqueraded as other websites, such as a German government website, Twitter, and a pro-Daesh website.. Typically, the sites and the inauthentic articles they hosted were built with scraped content and code elements from the target websites. The sites disseminated a range of critical narratives as well as false and misleading stories.

For an analysis and explanation of how we identified the 72 domains, see Appendix B: Domain Infrastructure.

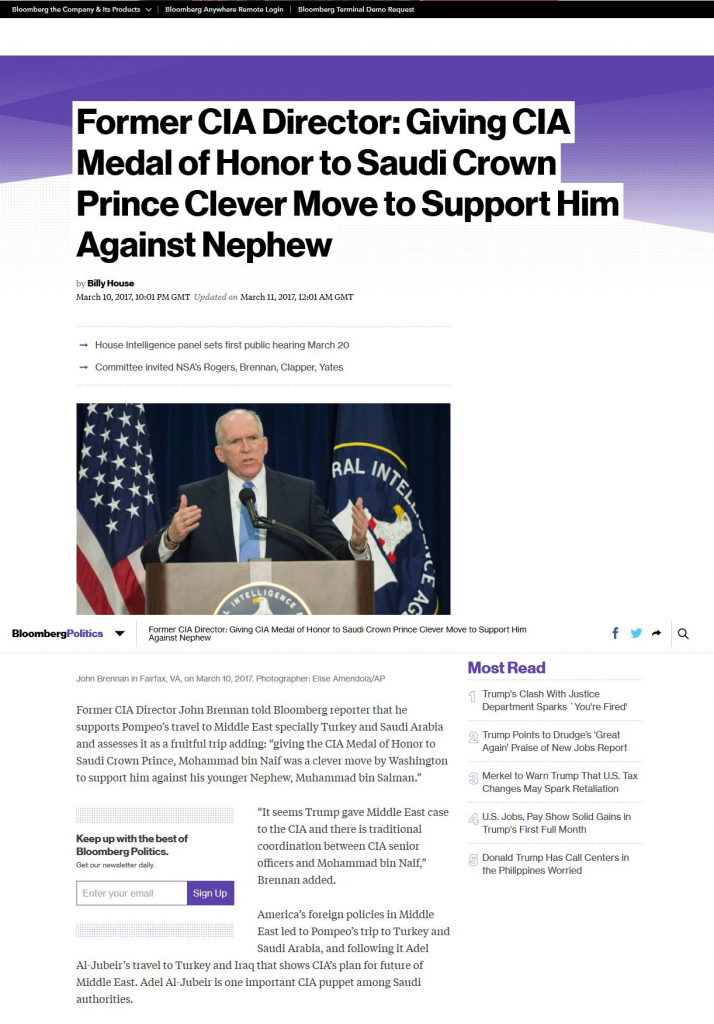

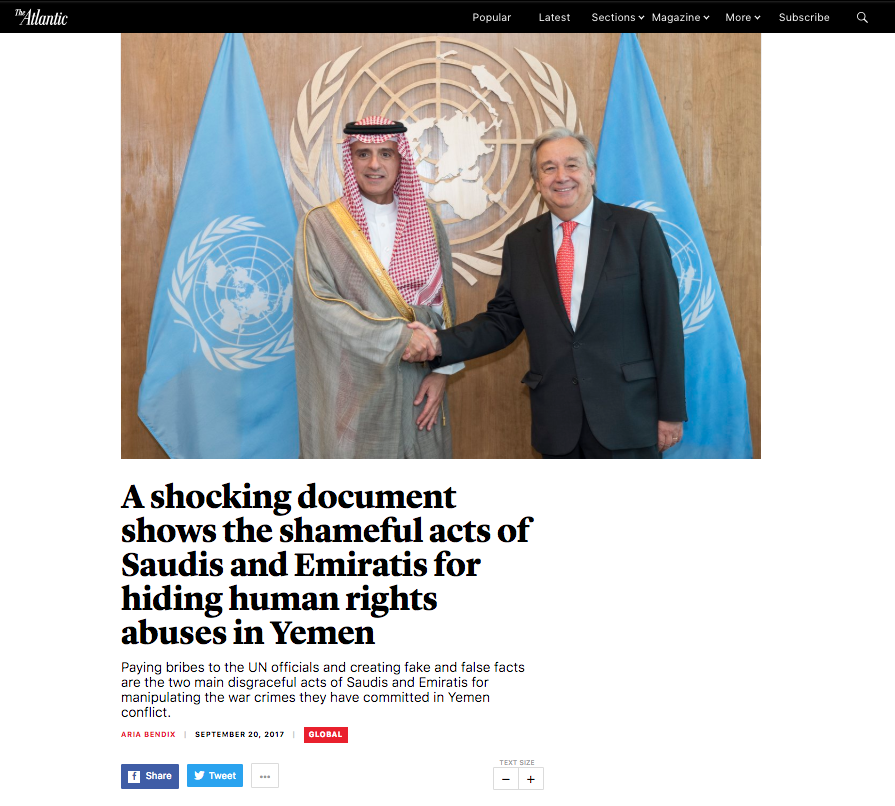

Most of the Endless Mayfly content is written with a dry and matter-of-fact tone, but in some cases the inauthentic content takes a more breathless, emotional approach. The writing tends to include grammatical and typographical errors, suggesting that it is written by non-native English speakers (see Part 2 for discussion of narratives). Figure 5 below depicts an example of the inauthentic content.

Typosquatting to Impersonate Existing Websites

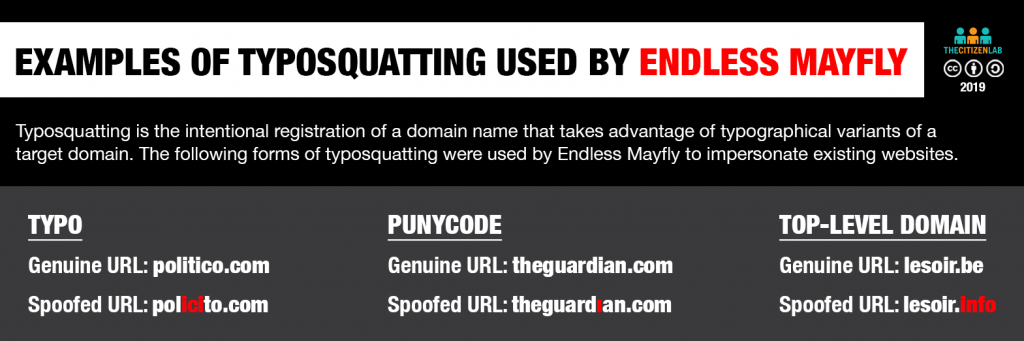

Endless Mayfly made extensive use of typosquatting, which is the intentional registration of a domain name that takes advantage of typographical variants of the target domain name. While typosquatting itself is not a new phenomenon and the registration of such domains may be legal, the technique is regularly used for criminal activities, phishing, and other dubious practices.

Endless Mayfly used three basic techniques to create lookalike domains (see Figure 6): typos, punycode, and different Top Level Domains (TLDs). In the simplest form of typosquatting, they simply added or reversed letters. In cases where media outlets did not control all TLDs associated with their name, they also acquired variants, such as the “.info” version of the target domain name.

Using punycode, Endless Mayfly replaced letters with look-alike characters to create visually identical domains. Punycode is an encoding scheme that allows so-called Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs), which use non-ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) characters, to be registered. It works by converting strings of Unicode (UTF-8) to the (ASCII) format.

Using punycode typosquatting, Endless Mayfly published content on domains like xn--theguardia-dq2e[.]com, which would display to the target as theguardiaṇ[.]com, or xn--huffngtonpost-69b[.]com, which would appear as huffıngtonpost[.]com.

Use of URL Redirects

In addition to the visual impersonation, URL redirects were used to point the root url to the target website being spoofed. This redirection adds an additional element to the deception. For example, accessing the root url indepnedent[.]co ( http://indepnedent[.]co/) would redirect to the Independent’s real domain, independent.co.uk. Any inauthentic articles hosted on the indepnedent[.]co would therefore still be accessible, while visiting the root url would take the user to the legitimate news outlet’s website.

| Typosquatted domain | Redirect URL |

|---|---|

| http://indepnedent.co | https://www.independent.co.uk/us |

| http://xn--emaraalyoum-1b9e.com | https://www.emaratalyoum.com/ |

| http://xn--telocal-xt3c.com | https://www.thelocal.ch/ |

| http://xn--alnaaregypt-cm8e.com | http://www.alnaharegypt.com/ |

| http://xn--c-wpma.com | https://www.cnn.com/ |

Table 3: Sample of redirects used by the typosquatted domains (checked on July 11, 2018)

Persona-Attributed Bylines Published on Third-Party Websites

Multiple Endless Mayfly personas also published articles under their names on unaffiliated third-party websites that allowed user-submitted content (Phase 2). For example, @Shammari_Tariq posted stories on China Daily, FairObserver.com, Buzzfeed Community, Medium, Opednews.com, and WN.com, among others.

In total, we documented 160 articles attributed to the personas, published on 20 mostly unaffiliated websites. While some, like FairObserver.com and OpenDemocracy.net, claim that there is an editorial review before publication, it is not clear how rigorous this process is.

The content of these articles followed the same themes as the rest of the campaign, such as criticism of Saudi Arabia. However, the articles also sometimes cited Endless Mayfly-created content hosted on the lookalike domains. For example, after publication of the inauthentic Local article alleging that six Gulf countries had asked FIFA to strip Qatar’s right to host the 2022 World Cup, persona @Shammari_Tariq published a post covering this false story for Buzzfeed Community. In the post, @Shammari_Tariq cites the inauthentic Local article as the source for the information and Reuters as having reported on it. Meanwhile @GerouxM published a post on Medium, reiterating the claim and citing The Local as the source.

In some cases, the persona whose byline was used to publish a user-submitted content story on a third-party site would subsequently promote it on Twitter. For example, the persona Brian_H_Hayden promoted “his” piece on ModernGhana.com over 270 times between August 22-23, 2017 on Twitter. Much of the promotion targeted reputable news sites, such as ITVNews in the UK, NDTV in India, and Reuters.

Step 4: Amplification of Content

Endless Mayfly used a range of techniques to amplify content, from using their Twitter personas to retweet and promote content to direct engagement with journalists.

While the websites and inauthentic content were typically amplified by the personas, in other cases we could find no public amplification by known Endless Mayfly accounts. We are unsure whether this reflected an incomplete action on the part of the operators, or that they may have been circulating the link via channels that we had not observed.

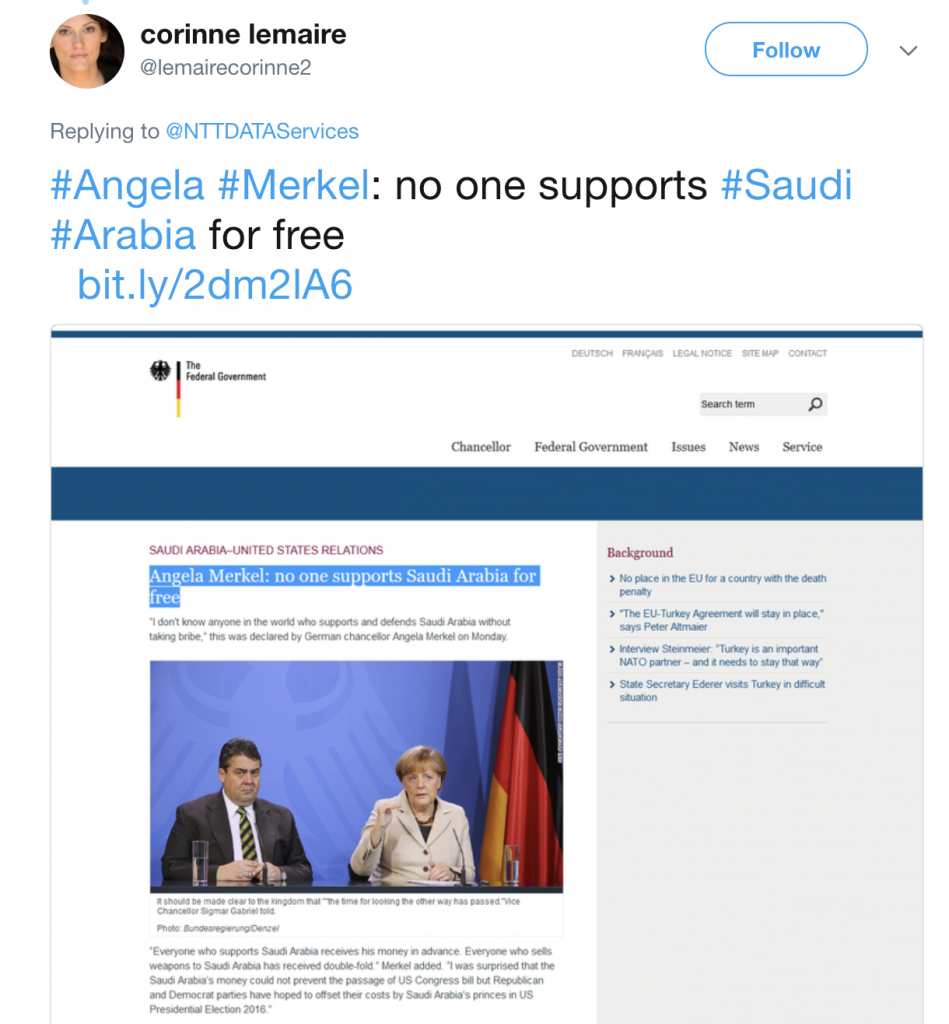

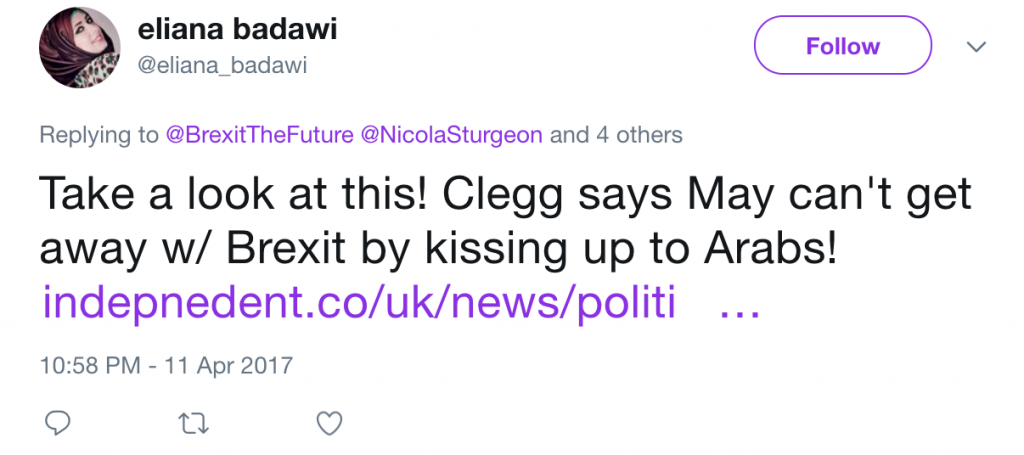

Personas Amplify Inauthentic Content on Twitter

Typically, once inauthentic content was published Endless Mayfly personas posing as activists, journalists, and students disseminated and promoted it on Twitter. Endless Mayfly Twitter personas repeatedly tweeted out links to the inauthentic articles, made strategic use of Twitter mentions5 targeting established journalists and activists, posted screenshots of the inauthentic articles, and sent private direct messages to journalists and activists.

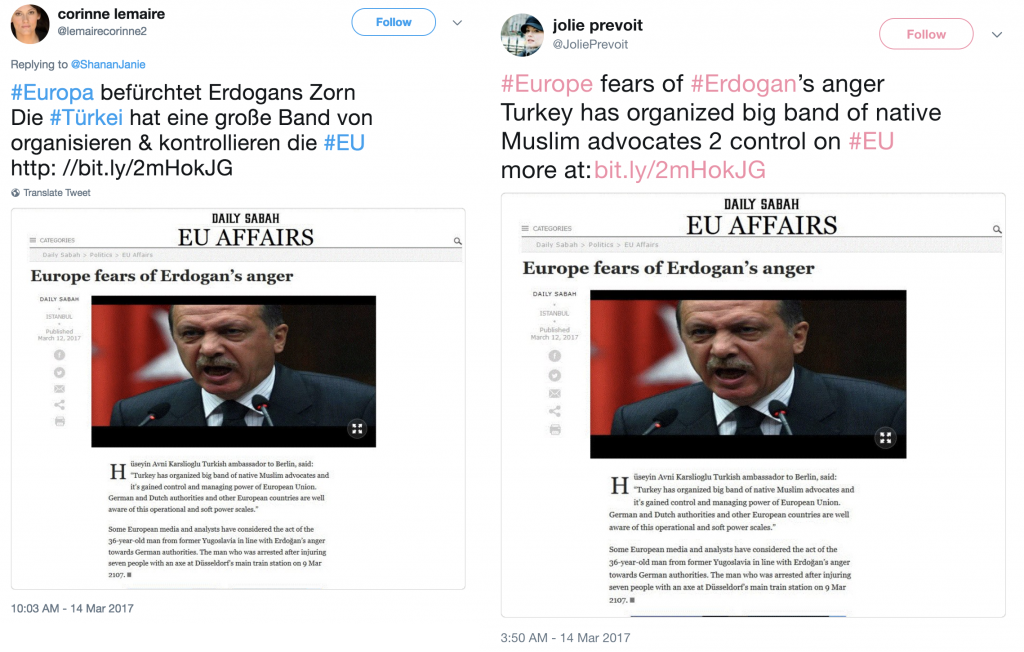

Sharing Screenshots of Inauthentic Articles

Endless Mayfly personas regularly included screenshots of the inauthentic articles in their tweets. By doing so, the message is conveyed even if the link is broken or if the viewer chooses not to click on the link. Recent studies have shown that users of social media tend only to read headlines, and that they often share a link without reading the body of the article. Screenshots therefore offer a backup to the link, increasing the likelihood that the message will be communicated. The message remains even though the evidence is ephemeral. Figure 9 below shows an example of this tactic.

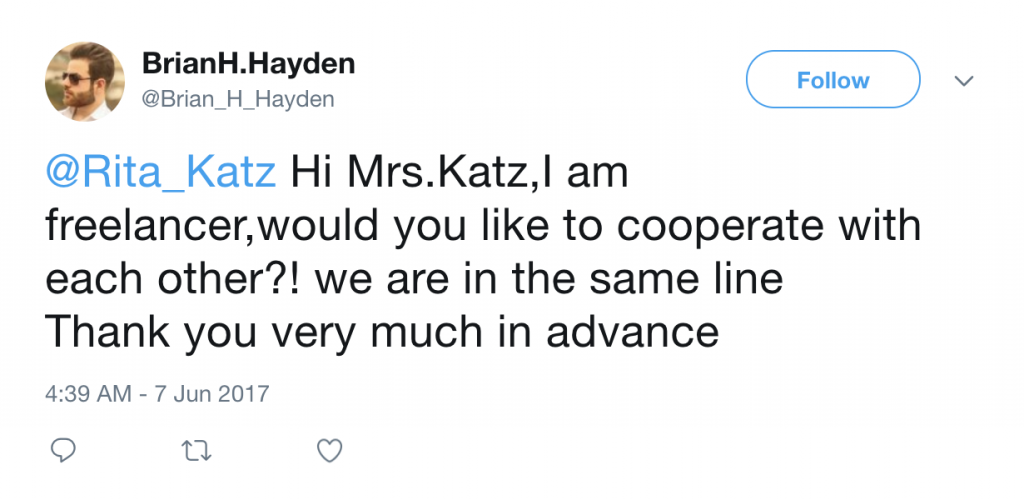

Publicly Engaging Real People on Twitter

During our investigation, we observed @Brian_H_Hayden reaching out to media outlets and journalists on Twitter, apparently seeking writing opportunities. Out of the 458 tweets published by the persona, at least 58 (12.7%) were in search of journalistic “collaboration.” The tweets would often claim that he was a reporter or ask for the recipient’s email address so that he could send them his work. See Figure 10 below for an example.

It is unknown if this tactic actually resulted in additional publishing opportunities or other forms of collaboration. Of the websites that did publish @Brian_H_Hayden’s articles, none had been publicly contacted via Twitter. The other personas who had articles attributed to them did not engage in this type of behaviour.

Furthermore, if a tweet begins with a user’s handle, it will not be displayed on the default view of a profile. This tactic makes a persona’s overt use of mentions to spread content and contact individuals slightly less visible and therefore less likely for users visiting the persona’s Twitter profile to perceive it as spammy or dubious. Unless someone clicks on the “Tweets and replies” tab, they will not see any of these types of tweets.

Privately Engaging Real People on Twitter

During Phase 4, we identified cases where personas engaged in direct messaging on Twitter to disseminate inauthentic articles. These cases include “Mona A. Rahman” (@Mona_ARahman), who had reached out to Saudi critic Ali Al-Ahmed, and “Bina Melamed” (@binamelamed), who had contacted and tweeted screenshots of her private conversation with Jerusalem Post reporter Amy Spiro. The former case was noted to us directly by Ali Al-Ahmed, while the latter case of direct messaging was identified when it was tweeted by Amy Spiro and again by Lahav Harkov when she was contacted by the same persona under a changed Twitter handle.

Twitter Bots Disseminate & Amplify Content

Between September 20-21, 2017, Endless Mayfly appears to have used a network of accounts on Twitter to amplify a hashtag critical of Saudi Arabia, #ShameOnSaudiArabia. These hundreds of Twitter accounts exhibited bot-like characteristics, such as usernames made up of a random string of numbers and minimal activity. In total, we recorded over 5,500 tweets and retweets with this hashtag. Of this number, 2,716 included a link to an inauthentic Atlantic article (see Figure 12). The article claimed to have news of a “shocking document” exposing human rights abuses by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in Yemen. Since our investigation, 83% of the 942 accounts that originated this traffic have been suspended by Twitter. The campaign’s activity is depicted below in Figure 11.

Despite the volume, it is uncertain how much impact the Twitter campaign yielded. Although the analytics affiliated with the Goo.gl shortlink6 used in this campaign tell us that there were 2,560 clicks, the inauthentic article could have been disseminated through other means, with a different link shortening service, or simply without a shortlink.

Iran-linked News Sites Propagate Falsehoods

In addition to the personas, a network of pro-Iran websites aided in the dissemination of the inauthentic articles. In total, we documented 353 pages across 132 domains that referenced or linked back to the inauthentic articles.

To determine the extent of this republishing network, we first performed a Google search of all the inauthentic articles’ URLs. This search returned a list of web pages containing backlinks to the inauthentic articles. In addition to the URLs, we also searched for the headlines of the inauthentic articles. We then scanned the links tweeted by the personas in our network, identifying pages that contained references or links to the articles.

This is not an exhaustive list, however, as data collection relied on the original language used in the headlines. In other words, we did not translate the headlines and then conduct a search using the translated text. For example, if an article’s headline had been translated into Russian and then referenced on a Russian-language website, it would not have been identified by our investigation. Furthermore, if a website is not indexed by Google, it is unlikely it would have been identified by us unless it had been referenced by the personas on Twitter.

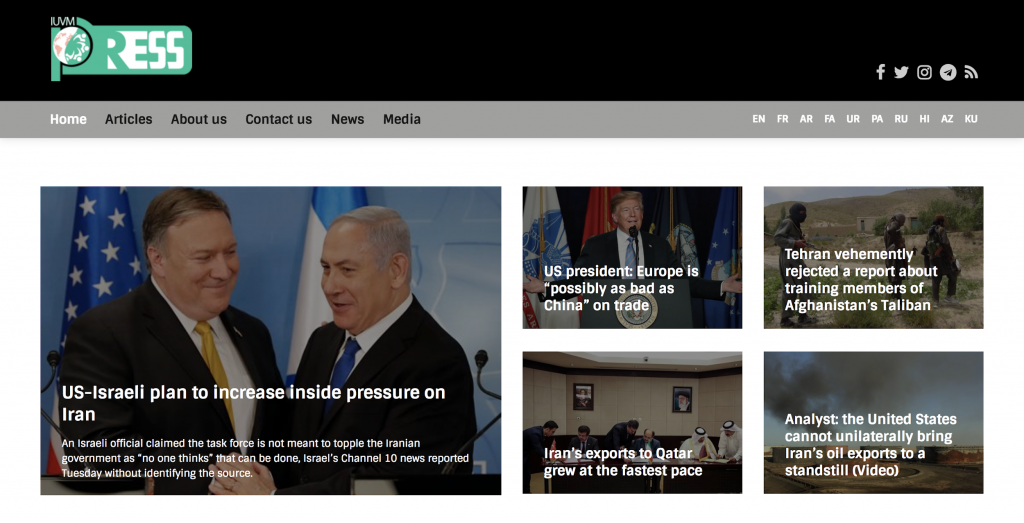

The top ten domains that most frequently referenced the inauthentic articles are listed below in Table 4. Of these ten domains, eight (IUVM Press, Whatsupic, AWDNews, Yemen Press, Instituto Manquehue, and RealNienovosti.com) all share the same IP address or registration details, indicating they may be controlled by the same actor. There is no overlap in registration information or IP addresses between Endless Mayfly and the republishing network, however.

| Site name | Number of link backs |

|---|---|

| IUVM Press* | 57 |

| AWD News* | 36 |

| Whatsupic* | 30 |

| Yemen Press* | 20 |

| Middle East Press* | 16 |

| Podaci Dana | 11 |

| Instituto Manquehue* | 11 |

| Liberty Fighters* | 10 |

| Real Nienovosti* | 5 |

| Rasid | 5 |

Table 4: Top ten domains that reference the inauthentic or persona-attributed articles identified by our investigation. * Indicates these sites either share the same registration information or IP address

Like Endless Mayfly’s personas, these websites claim to report on the news in an independent and unbiased fashion, but primarily push stories that align with Iran’s interests. For example, a PDF document titled “Statute” was found on iuvm[.]org that explicitly states that they are against “the activities and projects of global arrogance states, the imperialism and Zionism” and that “The headquarters of the Union is located in the Tehran –capital of Islamic Republic of Iran–.” A screenshot of IUVM (International Union of Virtual Media) can be found below in Figure 13.

Based on the number of inauthentic articles shared by the republishing network, it is reasonable to conclude that there was mutually supporting and possibly collaborative activity between the two groups.

Note: Republishing Network Suspended by Facebook, Twitter, and Google

In August 2018, in coordination with FireEye and through their own investigations, Facebook, Google, and Twitter announced that they had removed hundreds of accounts for “coordinated manipulation” linked to Iran. Many of these accounts were associated with websites that had been identified as part of Endless Mayfly’s republishing network.

For example, Instituto Manquehue, which FireEye details in their report, had either linked to or republished content from the inauthentic articles 11 times. According to FireEye, Instituto Manquehue had originally used the Iranian name servers damavand.atenahost.ir and alvand.atenahost.ir and had been registered with an email address that had also been used to register another Farsi-language website. Another website identified in FireEye’s report is Real Progressive Front, which also hosted several articles attributed to one of Endless MayFly’s personas.

In addition, investigations by Reuters and the Digital Forensic Research Lab found that IUVM Press, which is responsible for the majority of linkbacks and references to Endless Mayfly’s inauthentic articles, is also linked to the Iran-aligned operation first identified by FireEye. Similarly, the Project on Computational Propaganda at the Oxford Internet Institute found that of the accounts suspended by Twitter, IUVM Press was one of the top shared websites in Arabic and consistently pushed pro-Iran messaging.

Step 5: Deletion and Redirection

Typically, after the inauthentic articles were posted to Twitter, amplified by third parties, or covered by mainstream media, Endless Mayfly deleted the content and redirected visitors to the legitimate media outlets that they were impersonating. The redirects were usually removed after some time and the website taken down.

The Endless Mayfly content, however, would often remain in the caches of social media platforms, leaving a trail of posts that appeared authentic at a cursory glance. Although the links no longer pointed to the article, clicking on the associated links would lead to the genuine news outlet, until the websites were taken down completely. This deceptive technique further amplified the sense of a genuine story. In other cases, Endless Mayfly tweeted screenshots of the spoofed websites and their falsified content, further cementing the impression of a legitimate story.

Part 2: Endless Mayfly’s Preferred Narratives

This section provides an analysis of the most prominent narratives from the collection of inauthentic articles identified by our investigation.

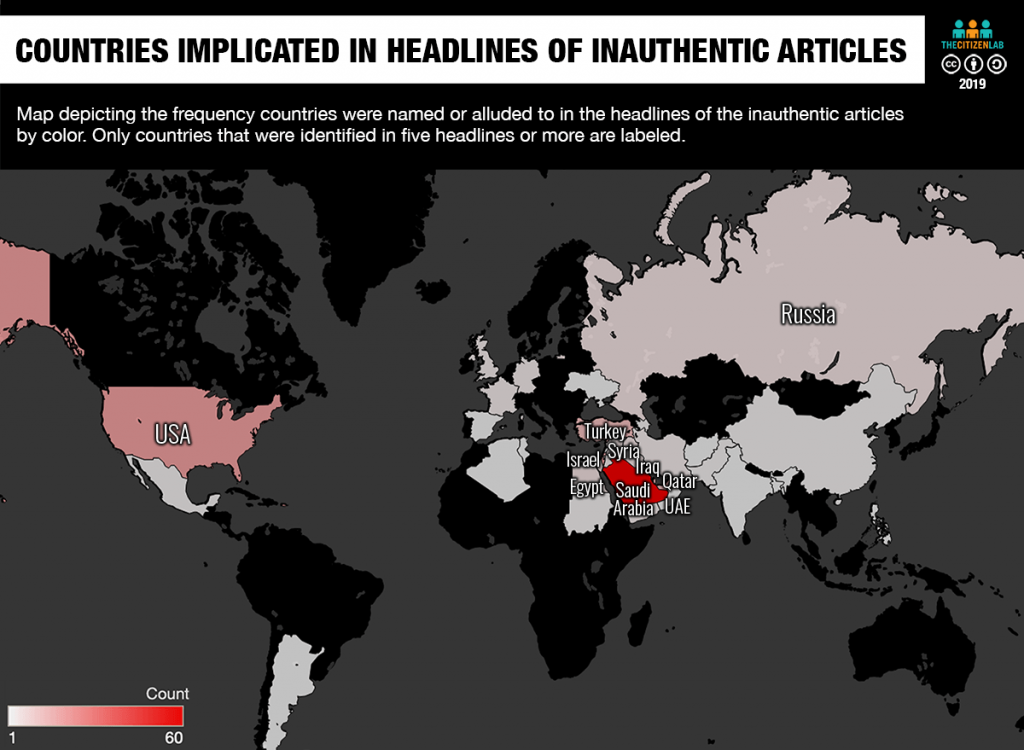

Endless Mayfly content is primarily focused on the Middle East, with a heavy emphasis on Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the United States. Saudi Arabia was either explicitly mentioned or alluded to in 61 of the 118 (52.6%) comprehensible7 headlines that we recorded. The second most mentioned country is the United States at 21 mentions, followed by Israel at 18 mentions. Figure 14 below depicts the frequency with which countries were implicated in the headlines.

Second, the articles are primarily concerned with geopolitical relationships and often name specific politicians or state actors, and were released to correspond with real world events. Of the 118 comprehensible headlines, only two did not mention or allude to a specific state, while 70 mention or allude to two or more countries in the same headline. One of the inauthentic Breaking Israel News articles, for example, uses Netanyahu’s genuine visit to Azerbaijan as context for the falsified quotes attributed to the director of Mossad.

Narrative analysis (see Appendix C for a description of our methods) yields three primary meta narratives in Endless Mayfly content: Saudi foreign relations are strained; the Arab states and Azerbaijan are cooperating with Israel; and Saudi Arabia supports terrorism.

Narrative 1: Saudi Arabia’s foreign relations are strained

Of the 99 inauthentic articles we were able to analyze,8 63 (63.6%) describe spurious events or fictitious comments attributed to various political actors. Over half of these deliberately pit Saudi Arabia against its allies and regional neighbours, such as the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. For example, 11 articles target Saudi-Qatar relations, six target Saudi-Egyptian relations, and six target Saudi-Turkish relations. These articles often name ambassadors, ministers, military leaders, or politicians and falsely attribute quotes to them that may be interpreted as hostile or provocative.

The remaining articles that seek to sow geopolitical discord tend to focus on Iranian interests, such as the Houthis in Yemen or tensions between Iran’s other adversaries, such as the United States or the European Union. One example is an inauthentic article impersonating the German federal government’s website, Bundesregierung.de. In the article, a quote is falsely attributed to Chancellor Angela Merkel that reads, “Germany will be the first country which will prefer its interests and national security to Saudi Arabia’s bribes.” Like the Twitter accounts and the rest of the inauthentic articles, this piece also blends elements of truth and fiction. While the quote from Merkel is false, the quote from Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel is accurate.

In addition, some of the articles’ jabs are subtle and hidden deep within the body text. For example, an inauthentic Alriyadh.com article describing Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and their plans to increase tourism initially comes off as mundane and almost benign. However, the last paragraph then alleges that this tourism strategy is in part due to Saudi Arabia’s plan to make Jeddah “outperform both Dubai and Doha” and become a “global city and business hub in the Middle East,” replacing the aforementioned cities in the UAE and Qatar.

While the use of divisive comments to pit nations against one another is certainly not a new phenomenon, it does stand out from recent media coverage of disinformation campaigns, which tend to focus on internal divisions within a domestic population, such as between progressives and conservatives, different ethnic groups, or supporters of opposing political parties. These articles also stand out from the clickbait-driven infotainment that have come to characterize Russian influence operations.

Narrative 2: The Arab states and Azerbaijan are cooperating with Israel

Fourteen of the inauthentic articles frame the relations between Israel and a number of Muslim-majority countries as friendly and growing. Of these 14, there is particular emphasis on relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia, with seven articles implying growing diplomatic, military, and economic cooperation between the two states. While Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Israel received the most coverage, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, and the area known as Kurdistan also receive some attention. These fake articles not only depict Israel’s footprint in the Middle East as expanding, but also frame the cooperating Muslim-majority states as willing actors in the relationship. An inauthentic Israel in Arabic article, for example, claims that Israel’s Chief Rabbi, Yitzhak Yosef, views the condolences of the Arab states for Shimon Peres’s death as a sign of Israeli-Arab rapprochement.

Narrative 3: Saudi Arabia supports terrorism

We identified nine inauthentic articles blaming Saudi Arabia for the rise of contemporary Islamist terrorism, often citing the Kingdom’s historical support of Wahhabism, a puritan interpretation of Islam, as the main reason. This is a common refrain from Iran-sponsored media and is a common accusation made by the Iranian government. The inauthentic Politico article, “New evidence for condemning Saudi Arabia in favor of 9/11 bill,” for example, falsely quotes Chuck Grassley, a senior United States Senator from Iowa, as saying there is definitive evidence proving Saudi Arabia’s direct role in promoting terrorism, and because of this evidence, legislation should be passed to allow the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attack to sue Saudi Arabia.

Part 3: Content Consumption and Impact

This section describes the results of the network’s activities in terms of content consumption and reactions from mainstream media.

Publicly available data from Twitter and link shorteners provide evidence that clicks and views were generated from the personas’ activity. Based on the 44 short links identified in our investigation, 21,686 clicks were generated by Endless Mayfly content. The distribution of clicks, however, was not uniform with three links making up 76.5% of all clicks, one of which was promoted with the aid of Twitter bots.

Both Goo.gl and Bit.ly’s APIs also provide data on the number of clicks by platform and country of origin. Based on the 44 short links, over half of the clicks originated from Saudi Arabia and approximately 20% from the United States. Regarding platforms, 68.2% of the clicks came from Twitter, 2.6% from Facebook, and 1.3% from iuvmpress.com, a pro-Iran media outlet we identified as part of the republishing network.

The complete set of short links identified by our investigation can be found in the datasets published with this article (see Appendix D).

Endless Mayfly content makes mainstream news

We identified three cases where an inauthentic article was mistakenly interpreted as legitimate news by mainstream media outlets, leading to propagation of false information, confusion, and public outcry. In each case, news outlets who inadvertently reported on the inauthentic articles had to issue retractions or updates on their website, while the news outlets being impersonated had to clarify that they were not responsible for the inauthentic articles.

In June 2017, Reuters reported that the six Arab countries that had cut ties with Qatar in June 2017 had written to FIFA, demanding Qatar be stripped of hosting the 2022 World Cup. However, this report was informed by an inauthentic article purporting to be Swiss newspaper, The Local. After Reuters had published their piece, several other media outlets, such as Global News, The Jerusalem Post, Bleacher Report, and Haaretz, also reported on the story, quickly propagating the false information. Reuters later retracted their story.

The two additional cases involved fraudulent Le Soir and Haaretz articles. The inauthentic Le Soir article, which alleged Saudi financing for President Macron, was circulated among several far-right French sites. Notably, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, a member of parliament for the far-right National Front party in France, tweeted a link to the inauthentic article (see Figure 16).

The inauthentic Haaretz article also achieved a degree of confusion and amplification, which claimed that family members of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev had invested some $600 million of personal wealth into the Israeli stock exchange. The article, and its deletion, were noted by Armen Press, who alleged that Haaretz had indeed published it but then purposely removed the “scandalous article,” implying a coverup instigated by the Azerbaijani government.

Part 4: Hints of a Malware Campaign

In July 2017, a website impersonating Twitter (twitter.com-users[.]info) was created by Endless Mayfly, which like the other domains in the Endless Mayfly network share similar or identical WHOIS registration information. The site hosted inauthentic profiles and tweets for prominent figures. We identified multiple instances of URLs that indicated spoofed tweets by Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman were fabricated.

A subdomain of the spoofed Twitter site (twitter.com-users[.]info/products/download) also hosted a number of malicious files mimicking legitimate Twitter clients for Android and Windows devices. This section briefly notes our observations about this malware.

| Name | Hash | Command and control |

|---|---|---|

| imo-signed.apk | 5b920c6cd1d8de54463f07965b8c43f3 | 217.182.54[.]223 |

| Android-Twitter.apk | 07d495245814c5c4996422b4b2f52473 | 217.182.54[.]223 |

| Desktop-Twitter.exe | 8522c77e48c846c2c026b6e16501a3b2 | 217.182.54[.]223 |

| mo_51_4444_ttps-signed(1).apk | bc31493e996db7fe45b7ed7aaa51fd54 | 51.255.101[.]144 |

Table 5: Malicious files found on the inauthentic Twitter site (twitter.com-users[.]info)

The binaries

The two first APK files (imo-signed.apk and Android-Twitter.apk) are encrypted metasploit payloads with command and control servers at the IP address 217.182.54[.]223. Metasploitis a penetration testing tool typically used to exploit vulnerabilities and compromised systems during security audits, in addition to providing ready-to-go malware with the ability to compromise systems and remotely control them.

Desktop-Twitter.exe is an encrypted Veil powershell binary for Windows machines. Veil is a tool that encodes Metasploit payloads in order to bypass antivirus signatures. The binary has a command and control server at the IP address 217.182.54[.]223.

The final file, mo_51_4444_ttps-signed(1).apk is an Android backdoor that communicates with a command and control server at 51.255.101[.]144. Once run, it downloads a jar code archive from hxxps://51.255.101[.]144:4444/xNL1OazI-Vs2jjWdb9mTVwPPb2kwBdOlj0zXiuIFzooL_6TclcIY8ggZE4qxO/, which is then loaded into memory and launched. Unfortunately, we were unable to retrieve this final payload.

Unknown targets

We have been unable to find evidence of infection attempts or victims, nor have we been able to identify these files in publicly available threat intelligence reports. Furthermore, the lack of contextual information makes it difficult to speculate about the targets or objective of the malware as it relates to Endless Mayfly. The presence of malware in a disinformation campaign, however, presents a concerning development in how current and future information operations may be conducted. In 2017, for example, a Russian disinformation operation, which we documented in our Tainted Leaks report, combined spear phishing tactics against specific individuals with the public dissemination of stolen material that was clandestinely altered by the operators. As information operations become more complex, the targeting of individuals with malware to steal private information, alter it, and then disseminate it on leaked sites to manipulate public opinion may become more common.

Part 5: Analysis of Competing Hypotheses

This section evaluates two hypotheses of the identity of the operator.

The people and institutions behind Endless Mayfly are not known to us, although a number of threat intelligence firms have connected related elements of the network to the Iranian government. This section briefly considers the evidence and logic between two hypotheses: that Endless Mayfly is Iran-aligned and that it is not. While we cannot conclusively prove either of these hypotheses, we find with moderate confidence that Iran or an Iran-aligned actor is the most plausible explanation based on the evidence we have gathered.

Hypothesis 1: Iran or an Iran-aligned actor

The narratives used by Endless Mayfly best fit the interests of Iran and its political rhetoric. In addition, Endless Mayfly has an apparently close relationship with a republishing network that has been linked by FireEye, other investigations, and social media platforms to an Iranian government-backed disinformation operation.

Narratives fit Iranian interests, propaganda

Endless Mayfly’s narratives systematically benefit Iranian interests or fit within familiar propaganda narratives already used by the Iranian government. For example, the extensive critical content concerning Saudi Arabia fits with themes that are regularly observed in Iranian public statements and propaganda.

In 2017, a study by Al Jazeera found that of the 1,400 and more political statements made by various foreign policymaking institutions in Iran, 80% of statements about Saudi Arabia “used critical and condemnatory language.” This observation is consistent with the Endless Mayfly personas, which frequently amplify content that frames the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in a negative light.

Framing Saudi Arabia as a creator and supporter of global Islamist terrorism is also a very common theme in Endless Mayfly content and is consistent with recent rhetoric from Iran’s top-ranking officials, such as Iran’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mohammad Javad Zarif, and their ambassador to the United Nations, Gholamali Khoshroo.

Notably, we were also unable to identify Endless Mayfly content that was critical, directly or indirectly, of Iran.

Links to other Iran-attributed operations

Not only is their content highly skewed towards pro-Iran and anti-Saudi Arabia, anti-Israel, and anti-United States messaging, it was primarily propagated by the same Iran-linked network that had been exposed by FireEye, Twitter, Facebook, and Google in August 2018.

Hypothesis 2: Unknown actor unaffiliated with Iran

It is possible that an unknown group unaffiliated with Iran is responsible for Endless Mayfly. Indeed, when the first few inauthentic articles were identified by journalists and researchers, there was some speculation that they were in service of Russian interests. This speculation was based on the narratives being amplified, the timing of their emergence, and other similarities with past Russian influence operations9. Anne Applebaum, for example, wrote a short piece for the Washington Post implying that the inauthentic Le Soir article accusing Macron of being funded by Saudi Arabia was linked to the Russians. She also had flagged one of the inauthentic Guardian articles as an example of “active measures,” a term referring to Russian attempts to discredit adversaries and influence world politics. A close analysis of the content produced by Endless Mayfly suggests, however, that this possibility is less than likely: not only is the content heavily focused on issues of concern to Iran, but some of the content is detrimental to Russian relationships and foreign policy.

While it is unclear what other nation-state actor would have the specific interests found in the Endless Mayfly content, it is worth considering whether a third party, such as a state wishing to discredit Iran or a commercial actor, might be responsible. However, the theory that this operation is an attempt to paint Iran as responsible for such an operation is not supported by any known evidence. Indeed, as many of the elements of the operation were active for years without exposure, and could potentially harm many of Iran’s rivals, it is difficult to see what value a third party would see in constructing such a “false flag” operation.

The theory that the operation might have a commercial motivation, meanwhile, is belied by the absence of monetization or advertising for the content.

Conclusion: Iran or Iran-aligned actor is the most likely hypothesis

During its many years of activity, Endless Mayfly produced extensive content that targeted Iran’s traditional adversaries by amplifying narratives that either frame these states in a negative light or imply discord between them and their allies. These narratives, which are consistent with Iran’s foreign policy goals and position on Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel, were propagated by a republishing network that has been attributed to Iran by multiple independent groups. Finally, we find no evidence supporting the possibility that the operation was a false flag, or that it was the product of commercial interests. We thus conclude that Hypothesis 1, Iranian sponsorship of the operation, is the most plausible.

Part 6: Discussion

This section examines some of the key issues raised by the findings of our investigation. We focus on the challenges associated with investigating and countering disinformation in an environment that allows for easy experimentation and where evidence is not only deceptive but ephemeral.

Endless Mayfly likely had multiple goals, including achieving direct “buzz” on social media and getting their content “picked up” by major news outlets. Their record of success is equivocal. While in several cases Endless Mayfly was successful, in many others their operations gained little traction. With respect to media coverage, however, we have identified at least three cases in which Endless Mayfly content resulted in mistaken amplification by genuine news outlets. Although this amplification was short lived, and often resulted in quick corrections and debunking, these cases no doubt provided them with useful experience with what works and will likely lead to future experimentation.

While Endless Mayfly may not have achieved the success they hoped for, they are a case study for how disinformation operations adapt and how they make use of existing, persistent narratives.

Persistent narratives can frustrate control measures

Although digital disinformation campaigns may experiment with novel tactics and strategies, the narratives they rely on typically draw from familiar tropes and long-standing beliefs. Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, for example, played on existing fears to create divisive messages, while information operations during the Brexit referendum pushed xenophobic narratives that stoked already heightened fears of immigrants. In the case of Endless Mayfly, the articles echoed already existing concerns in Iran, such as Saudi Arabia’s growing relationship with Israel. As Jarred Prier observed, propaganda relies on existing narratives, even if they are obscure.

The persistence of narratives, therefore, poses additional challenges to countering disinformation. First, even if a technological solution is effective in preventing the dissemination of disinformation, and provided the actors do not find another workaround, the narrative may still remain and can be co-opted for malicious means at a later date. A 2017 study comparing the various strategies adopted by European states to counter Russian information operations found that there is no clear consensus on how to address narratives, with only a few select countries actively confronting the narratives pushed upon them. Furthermore, the effectiveness of directly countering a narrative can backfire, bringing more attention and legitimacy to the message one is trying to negate in the first place.

Second, in disinformation campaigns, narratives often begin as push factors (i.e,. pushing a narrative onto someone), but once established can act as a pull factor. In a research report commissioned by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, James Pamment et al. note that, once a narrative becomes ingrained, it becomes self-stabilizing in that “people tend to shy away from input that threatens the narrative’s integrity.” An affinity for information that confirms our preconceptions can, therefore, lead to cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias, two phenomena that also contribute to filter bubbles and echo chambers, and selective sharing.

Challenges of ephemeral evidence

The transient nature of Endless Mayfly’s tactics, content, and social media accounts proved to be an additional challenge for the investigation, alongside the already deceptive means by which disinformation campaigns are conducted. The result was content that is not only designed to deceive, but evidence that was ephemeral. Of all the inauthentic articles we documented, for example, none remain accessible save for those which were archived or cached. Redirects that were once employed were also deleted, along with several Twitter accounts, and some persona-attributed articles.

Ephemeral disinformation may frustrate investigators attempting to get a complete view of a network’s activity, leading to possible misattribution and further confusion. While a handful of fraudulent web pages are helpful as starting points for an investigation, an assessment of a network’s “chain-of-events” is required to gain meaningful insight into such an operation. A narrow data set can result in misrepresenting the influence operation’s actual target, strategy, objectives, and narratives, as was the case when the initial inauthentic articles emerged in Western news media. And in the case of one of the inauthentic Haaretz articles, the redirects employed and eventual takedown of the content led Armen Press to speculate that this was all part of a conspiracy to cover up damaging information about the Azerbaijani president and his family.

Finally, ephemeral disinformation is clearly designed to elude detection. Because the evidence linking seemingly separate events or accounts is temporary, investigators may be unable to make the necessary connections that would detect an influence operation or correctly identify the reach and depth of the operation. This tactic buys the operators time to pursue their objectives and experiment. Endless Mayfly has been active for years despite being detected by multiple individuals and news outlets.

Part 6: Conclusion

Based on the evidence gathered from our investigation, we conclude with moderate confidence that Iran or an Iran-aligned actor operating the Endless Mayfly network systematically attempted to influence global perceptions, presumably to achieve geopolitical outcomes, using a stream of false and misleading content. The campaign was neither strikingly clever nor particularly sensitive to the culture of the intended audience. However, it eluded blocking and detection for years, generated some social media engagement, and achieved a few successful cross-overs into mainstream news.

The geopolitical, cultural threats posed by Endless Mayfly are difficult to measure. It is unclear how much demand they generated for the stories and narratives they were promoting, or whether they had a meaningful impact that swayed public opinion. Competing in the “attention economy” is difficult and it is likely Endless Mayfly failed to achieve the kind of impact that its operators and backers hoped for.

Although Endless Mayfly employed tactics similar to other known influence operations, such as false content and inauthentic personas, it is distinguished by its strategic use of redirects and content deletion—a technique we describe as “ephemeral disinformation.”

The Online Disinformation Laboratory

The Internet has arguably become a “disinformation laboratory,” where everything from tools to messaging can be tested with an eye to maximize impact and elude detection. Because some of the most widely used online spaces have become data-driven platforms for digital marketing, we suspect that many disinformation operations now mimic online marketing campaigns and tweak their content to maximize views, clicks, or shares. Disinformation operations can therefore quickly adopt and discard tools and tactics, and regularly tweak their operations to maximize impact and reach.

The agility afforded by online platforms creates a “whack-a-mole” problem for disinformation control efforts. Technological solutions, such as identifying specific patterns and actors, and blocking their personas and accounts, tend to be reactive. When one account gets banned, another emerges. When one botnet is exposed, another is created. Where one tactic fails, another can be tried. Furthermore, the efficacy of content moderationand fact-checking remain debatable, with little research on how these techniques affect multi-platform information campaigns.

Endless Mayfly illustrates how much we have yet to learn about the practices and players involved in disinformation, and the challenges of attribution when faced with incomplete and fleeting evidence. The study of such operations is useful in better understanding not just the technical tools and tactics used in disinformation, but the types of narratives being employed and the audiences being targeted. Research on the creation and dissemination of disinformation (the supply side) has come a long way, but the effects and patterns of consumption (the demand side) are far less well understood. This case study and more like it are useful to help us understand why and how information operations are used. We hope this report will give other researchers studying information operations a useful framework to build upon for their own investigations.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to MrObvious, Alexei Abrahams, Siena Anstis, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Alok Umesh Herath, Adam Senft, and Mari Zhou.

Appendix A: Timeline of The Endless Mayfly Network

Appendix A describes the four phases that make up the network’s activity from April 2016 to November 2018, including the tactics and strategies employed.

Phase 1 – The Peace, Security, and Justice Community

(April 2016 – April 2017)

Between April 2016 and April 2017, Endless Mayfly employed six personas on Twitter clustered around the “Peace, Security, and Justice Community” account (@PSJCommunity on Twitter), a fake anti-Saudi Arabia organization. See Figure 17 below for an example tweet from one of the personas.

During this period the network promoted at least 64 inauthentic articles, disseminated by six accounts. See Table 6 below for list of accounts

| Twitter handle | Location | Creation date | Twitter bio |

|---|---|---|---|

| JoliePrevoit | Paris | 12/4/2016 | “freelancer;hyperpolyglot:Deutsch,English,un poco español,français,un po ‘di italiano,العربية;#HumanRights & civil society activists, advocates for reform,” |

| lemairecorinne2 | N/A | 12/6/2016 | None |

| marcelle_geroux | London | 11/7/2016 | “Journalist, Reporter and Phd student of International Relations, works for @PSJCommunity” |

| eliana_badawi | Europe | 3/8/2016 | “freelance journalist, Muslim, anti-Wahhabism (terrorism), works at @PSJCommunity” |

| LinaVincent91 | Paris | 4/1/2017 | “Journaliste, traductrice, écrivain. @PSJcommunityFR #Arabiesaoudite #Wahhabisme #Daech #alQaeda #MoyenOrient” |

| gabrielblanc4 | Paris | 16/2/2017 | “Journaliste. J’étudie les langues étrangères , actuellement le Moyen-Orient, notamment l’Arabie Saoudite. Je suis fin prêt à coopérer avec les agences.” |

Table 6: Phase 1 personas and their associated Twitter accounts

@PSJCommunity and its affiliated personas

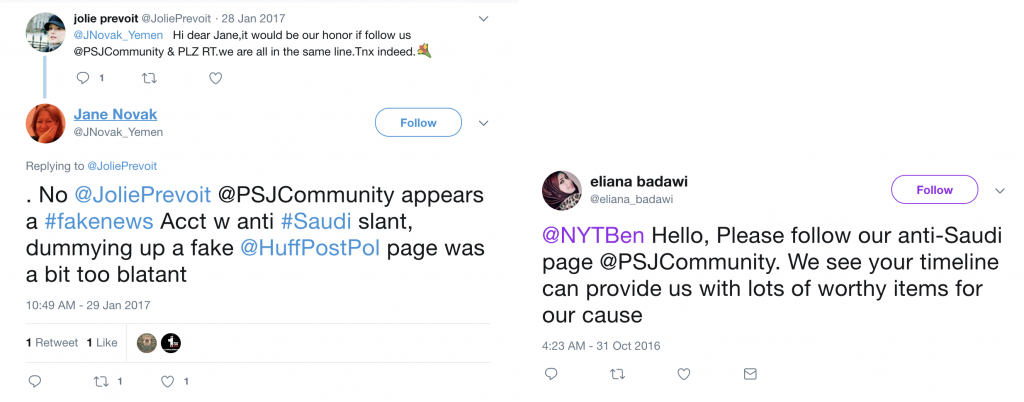

The Phase 1 personas are linked by their engagement with the “Peace, Security, and Justice Community” (see Figure 18). The account portrayed itself as an “independent community,” while the affiliated personas10 posed as journalists, students, or civil rights activists. The personas and @PSJCommunity routinely amplified third-party content critical of Saudi Arabia, while simultaneously disseminating their own inauthentic content.

In addition to directly disseminating content, Endless Mayfly personas regularly engaged uninvolved accounts, presumably in an effort to convince them to follow @PSJCommunity (see Figure 19).

Endless Mayfly’s Web Presence: Impersonating News Outlets

During this phrase, we tracked 64 inauthentic articles that spoofed well-known media outlets, such as Haaretz, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, Bloomberg, and The Atlantic. All domains employed typosquatting, such as using a common misspelling (ex. theatlatnic[.]com) or a different top-level domains (theglobeandmail[.]org instead of theglobeandmail.com).

| Example target domain | Example typosquatted domain |

|---|---|

| theguardian.com | theguaradian[.]com |

| independent.co.uk | indepnedent[.]co |

Table 7: Examples of lookalike typosquatting employed by Endless Mayfly in Phase 1

Phase 2 – New personas, third-party bylines, new typosquatting, and malware

(April – October 2017)

Between April and May 2017, the original six Endless Mayfly Twitter accounts, including @PSJCommunity, went silent. They were replaced with four new Twitter accounts posing as journalists and activists (see Table 8). Like the Phase 1 personas, they tweeted links to inauthentic articles, over 55 of which were created during this period. As with Phase 1, after amplification, the articles were deleted and the links redirected to the genuine domain being impersonated.

| Twitter handle | Location | Creation date | Twitter bio |

|---|---|---|---|

| @OSaeedFJ | London | 6/4/2017 | “Freelance Journalist, interested in politics and international relations; from so-called Saudi Arabia (wish it were Republic of Arabia)” |

| @Shammari_Tariq | New York | 27/4/2017 | “Online Activist | Covering the latest from Saudi Arabia | Freedom. Justice. Equality. Let’s get to work!” |

| @GerouxM (Note: This is a new Twitter handle associated with the same “Marcelle Geroux” persona from Phase 1) | London | 15/5/2017 | “PhD. candidate, Politics and International Studies, SOAS University” |

| @Brian_H_Hayden | Paris | 21/5/2017 | ”freelancer;hyperpolyglot:Deutsch,English,unpoco español,français,un po ‘di italiano,العربية;#HumanRights & civil society activists, advocates for reform.” |

Table 8: Documented Phase 2 personas

The articles were predominantly written in English and Arabic, and followed similar narratives to Phase 1. In addition, the personas sought bylines on unaffiliated sites like Buzzfeed that allowed for user generated content.

Personas Seek Bylines on Unaffiliated Sites

During Phase 2, we documented 160 persona-attributed stories published on third-party platforms. Endless Mayfly selected third-party sites that enabled user-generated or “community” publishing. Typically these publications further amplified Endless Mayfly inauthentic content, creating an echo effect for the initial false claims.

Enter Punycode Typosquatting

While most Endless Mayfly content during Phase 2 was published on typosquatted domains, such as thejerusalempost[.]org (mimicking jpost.com), they also adopted punycode typosquatting during this phase.

Phase 3 – Bots amplify #ShameOnSaudiArabia and drive traffic to inauthentic Atlantic article

(August – November 2017)

The creation of inauthentic and persona-attributed articles declined sharply in Phase 3. However, during this period it became apparent that Endless Mayfly was using Twitter bots to amplify their messaging. This included promoting the #ShameOnSaudiArabia hashtag and an inauthentic article purporting to provide a “shocking document” about Saudi Arabia.

Phase 4 – Diminished but ongoing network activity

(December 2017 – November 2018)

Although activity declined significantly after Phase 3, it did not stop. In 2018, we observed a revival of Endless Mayfly personas on Twitter and of their republishing network. During this time, we tracked several inauthentic articles mimicking the Times of Israel, the Belfer Center, and Breaking Israel News. In addition, new personas surfaced on Twitter to disseminate the articles using Twitter mentions and, in the case of Ali Al-Ahmed and Amy Spiro, direct messages.

The relatively limited activity in 2018 suggests that Endless Mayfly may have been re-evaluating their strategy and tactics, or diverting their resources elsewhere. Bot activity and malware, which were only seen once during our investigation, did not make a reappearance. However, the use of personas purporting to be writers or activists has continued alongside the creation of new inauthentic articles, indicating that these tactics may have borne more desired results.

| Twitter handle | Location | Creation date | Twitter bio |

|---|---|---|---|

| @Mona_ARahman | London | 23/2/2010 | “Political Analyst & Writer” |

| @binamelamed | London | 18/1/ 2010 | “Human rights activist, Freelance journalist, Enjoy politics, activism and martial arts.” |

Table 9: Phase 4 personas on Twitter

Appendix B: Domain Infrastructure

We employed two methods to identify the network of domains used by Endless Mayfly. The first involved using RiskIQ’s PassiveTotal to search both for domains registered with the same WHOIS information and for domains hosted on the same IP addresses. The use of the same registration information reflects an incomplete compartmentation of each operation by the Endless Mayfly operator. For example, the email address jackson.mariani[@]mail.ee was also used to register nationalepost[.]com, foriegnpolicy[.]net and theglobeandmail[.]org.

In addition to searching for similar WHOIS information through PassiveTotal, we also recorded the typosquatted domains that were tweeted by the personas. Through these two methods, we identified 72 different domains linked to this operation between September 2016 and November 2018.

In mid-June 2017, the operators continued to register typosquatted domains, but employed punycode to mimic genuine domains. For example, xn--israelinarabi-ugb[.]com or xn--sraelinarabic-29b[.]com were registered to mimic www.israelinarabic.com.

Around March 2017, they started to use Cloudflare as caching servers for their end servers, likely as a way to hide their hosting infrastructure.

To identify the architecture, we checked which IP was hosting a domain name using RiskIQ’s passive DNS database. The following table summarizes the list of IPs used in this campaign:

| IP | Provider | Type | First seen | Last seen | Number of articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66.96.147.118 | Endurance | Shared Server | 2016-10-20 | 2017-04-18 | 23 |

| 185.148.144.161 | BelCloud | Shared Server | 2017-05-31 | 2017-10-16 | 18 |

| 67.225.208.62 | Liquid Web | Shared Server | 2017-05-19 | 2017-07-08 | 11 |

| 31.170.164.116 | Hostinger | Shared Server | 2016-10-04 | 2016-11-06 | 8 |

| 198.50.224.232 | OVH | Shared Server | 2017-04-15 | 2017-04-23 | 7 |

| 185.148.144.3 | BelCloud | Shared Server | 2017-05-20 | 2017-06-13 | 5 |

| 66.96.147.105 | Endurance | Shared Server | 2017-01-25 | 2017-04-19 | 4 |

| 66.96.147.102 | Endurance | Shared Server | 2017-01-17 | 2017-07-25 | 2 |

| 66.96.162.135 | Endurance | Shared Server | 2017-02-05 | 2017-02-05 | 1 |

| 185.176.40.63 | Zetta Hosting | Shared Server | 2017-02-24 | 2017-02-24 | 1 |

| 200.74.241.181 | Level 3 | Shared Server | 2017-02-18 | 2017-02-18 | 1 |

| 31.170.164.235 | Hostinger | Shared Server | 2017-02-18 | 2017-02-18 | 1 |

| 141.8.225.237 | Confluence | Shared Server | 2016-10-19 | 2016-10-19 | 1 |

| 104.219.248.118 | NameCheap | Shared Server | 2018-06-25 | 2019-04-10 | 1 |

| 198.54.114.178 | NameCheap | Shared Server | 2018-11-12 | 2019-04-10 | 1 |

Table 10: List of IPs used in this campaign. Most articles were hosted either on Endurance’s network, likely through their brand iPage, or on BelCloud through their brand TrueHoster

Appendix C: Narrative Analysis

In order to distill the most prominent narratives from the data set, all 135 articles were organized into the categories below. The categories were determined after an initial reading of all the articles. Two rounds of coding were conducted. In the first round, the two researchers coded each article independently, achieving 71% intercoder reliability. A second round of coding was then conducted by the same researchers to resolve any discrepancies.

Note: Discourse analysis was conducted in English. Where articles were written in French or Arabic, their English translations were used.

| Category | Number of articles | Category description |

|---|---|---|

| Geopolitical discord | 63 articles (46.7%) | The article describes events, actions, or statements made by government officials towards a foreign state that may be construed as provocative, hostile, or counter to the foreign state’s interests. |

| Domestic discord | 16 (11.9%) | The article describes events, actions, or statements made by political actors that may sow discord between political parties or actors within the same state. |

| Cooperating with Israel | 14 (10.4%) | The article describes events, actions, or statements made by political actors or government officials that show cooperation between Israel and another state. |

| Saudi Arabia supports terrorism | 9 (6.7%) | The article describes events, actions, or statements that either link Saudi Arabia to terrorist activity or allege that Saudi Arabia supports terrorism. |

| Other | 5 (3.7%) | The article does not fit into any of the categories. |

| No archive | 31 (23%) | The article cannot be coded because it no longer exists and there is no cache, screenshot, or copy of the text to perform any meaningful analysis. |

| Copy of existing article | 5 (3.7%) | The article is a direct copy/paste of an already existing real article. |

Table 11: The categories used to code all 135 articles identified by our investigation. Note that some articles take on more than one category

After coding all the articles using the above categories, we removed the articles coded as “No archive” or “Copy of existing article.” We then conducted a discourse analysis on the 99 remaining articles’ headlines and body texts by comparing the events, actors, and countries identified in the articles with relevant and real events, alliances, policies, and geopolitical history. In addition to this analysis, we did fact-checking on any claims in the articles.

Based on these 99 articles, we determined that the three most prominent metanarratives were: 1) tension between Saudi Arabia and its allies and neighbours is growing; 2) Israel is increasing cooperation with the Arab states and Azerbaijan; and 3) Saudi Arabia supports or is responsible for terrorist activity.

Appendix D: Campaign dataset

Below are links to the data generated from our investigation and used in our analysis. This dataset includes the following CSV files:

- domains.csv: List of domains registered by the operators

- fake_articles.csv: List of fake articles published by the operators

- personas_bylines.csv: List of articles published on open platforms by personas used in this campaign

- 3rd_party_articles.csv: List of articles published on third-party websites based on fake information published in this campaign

- Short_urls.csv: List of short links used by the personas that redirected to the inauthentic articles

- Personas Twitter activity [folder]: Personas’ Twitter activity pulled from Twitter’s API

While we are aware that the data above is partial, it is representative of some of the strategies and tactics employed by this campaign and may be useful for other researchers conducting their own investigations.

You can download the full dataset on GitHub: https://github.com/citizenlab/endless_mayfly

You can also find Indicators of Compromise for the malware used in this campaign in the Citizen Lab Indicators github repository: https://github.com/citizenlab/malware-indicators

- The name “Endless Mayfly” was chosen to reflect both the network’s ephemerality and seemingly unending activity. Mayflies belong to the order Ephemeroptera and are named so because of their brief lifespans.

- The Twitter account associated with “Bina” changed their handle to “LeakersWB” and was suspended shortly after.

- For the purposes of this report, a persona is defined as a distinct character distinguishable by their online name, associated Twitter account, and self-ascribed descriptors. For example, the persona @Shammari_Tariq refers to themself as Tariq Al Shammari, has penned articles under that name, and describes themself as a student at the State University of New York.

- Persona bylines are articles published under a persona’s name.

- Twitter mentions are tweets that include another account’s handle, allowing the personas to target specific users that may be more receptive to their messaging (e.g., activists critical of Saudi Arabia’s human rights record).

- A Goo.gl shortlink was used to mask the original link (hxxp://theatlatnic[.]com/international/archive/2017/09/shocking-document-shameful-acts-saudi-emiratis-cover-human-rights-abuses-yemen/549410/). However, in April, 2019, Google discontinued its shortlink service, which also meant that any existing shortlinks and their affiliated statistics were taken down.

- In some cases, we observed evidence that an inauthentic article existed, but because it was taken down before an archive or screenshot was taken of it, no headline or body text could be used for discourse analysis. For example, alryiadh[.]com/1594373 was identified through a Google search of the domain. Because it was indexed by Google, this implied that it existed at one point. However, it had already been taken down and no cache of it existed.

- Although we recorded 135 inauthentic articles, we were only able to code and analyze 99 of them. The other 36 were either copies of existing authentic articles or were not cached or archived in time for us to conduct narrative coding. In other words, while we have evidence that these inauthentic articles existed, there was no body text for us to analyze. This number is less than the number of comprehensible headlines analyzed because some articles had enough evidence of a headline (either through a tweet or screenshot), but no accompanying body text.

- Buzzfeed News’ analysis of one of the inauthentic Guardian articles indicates that there may have been a 12th persona named “Addilyn Lambert.” They translated multiple inauthentic articles into Russian, which were then published by Russian-language news sites.

- All personas identified in Phase 1 were affiliated with @PSJCommunity, either by explicitly stating so in their bios or by actively recruiting followers for the account. The Twitter accounts @LinaVincent91 and @eliana_badawi, for example, both listed PSJCommunity in their bios, whereas the persona @JoliePrevoit actively recruited followers for PSJCommunity and mentioned them with notable frequency. Out of 3,477 tweets, mentions, and replies by @JoliePrevoit between April 20, 2016 to May 13, 2017, 1,038 included “@PSJCommunity.” 298 explicitly included the phrase “follow us @PSJCommunity.”